In his paper Policy Entrepreneurship at the White House: Getting Things Done in Large Organizations, Thomas Kalil identified a number of “Skills and Dispositions” that are necessary for success.

Kalil’s List of Skills and Dispositions

While Kalil’s paper used the term “Skills and Dispositions,” these descriptions are actually more akin to Personas—a ‘hat you wear’ or a role you take on within a specific context.

I quote Kalil’s list of Skills and Dispositions below, with the descriptions lightly abridged:

- The Diplomat: Has the ability to act as an honest broker to resolve interagency disputes or help agencies reach consensus on a policy issue. This is critical because a lack of consensus can delay progress on an idea or initiative.

- The Visionary: Has the ability to generate or spot good ideas. In the White House, this is especially valuable in the run-up to the budget, major policy addresses, and presidential or cabinet events. They have the ability to get excited about others’ ideas, not just their own, which dramatically increases the number of ideas they can advocate for.

- The Advocate: Has the ability to be an effective champion for the president’s priorities. This requires the ability to explain in a compelling way why something is a priority and what individuals and organizations can do to advance it. This is important because presidential decisions are rarely self-executing and may require action by Congress, federal agencies, state and local governments, the private sector, and civil society.

- The Communicator: Has the skill of clear and concise oral and written communication with multiple audiences. A communicator also has a solid understanding of what different audiences are looking for. This requires having empathy for the individual you are collaborating with and the ability to ask what motivates them and how they define success in their role. It requires establishing the context needed for them to understand your idea; avoiding jargon, special vocabulary, or acronyms they are unlikely to understand; and knowing what “mental models” they use to make sense of the world.

- The Student: Is comfortable as a generalist when necessary and can quickly get up to speed on a new issue. This is particularly important in an environment where individuals may have a broad portfolio and must respond to varied crises or external events.

- The Recruiter: Identifies people who should be working for the government or are a good fit for newly created positions. The recruiter is more likely to steer than row and, like Tom Sawyer, is able to get colleagues and associates to help “paint the white picket fence.”

- The Organizer: Follows up on the status of a commitment to an action item and tracks the next steps.

- The Connector: Builds networks of people who can help generate ideas. The connector helps prevent surprises and finds out what is really going on inside other organizations.

Every Policy Team has Personas

Kalil’s list of “skills and dispositions” emerged from his work at the White House, where they had a policy-setting role and relied on other branches of government to implement the President’s agenda. Policy Teams similarly rely on partner teams like Product and Customer Service to ensure that policies come to life in the customer or user experience.

Depending on the scope and breadth of your team’s remit, you will likely need to adapt or tailor the personas in Kalil’s original list and supplement them with personas that are relevant to your team.

Some potential additional personas are provided below.

- The Worker Bee. The operations core of the team. Can be relied upon to efficiently churn through cases or queues of work that require attention to detail and subject matter expertise within a well-defined area.

- The Doer. Can be counted on to get things done, either individually or as the lead on an initiative or a project team. Unlike the Worker Bee, who specializes within a defined area, a Doer drives projects and initiatives of varied scope and complexity. They are both incisive and decisive; when placed in a new situation, they ask the right questions, figure out what’s important, and see the work through to the end without getting bogged down by things that would ordinarily block people. They are what Conor Dewey describes as “Barrels” in his post, Barrels and Ammunition.

- The Scribe. Adept at recognizing, documenting, and organizing tacit knowledge—information about “how we work” or “how decisions are made here”—that is typically acquired through years of practice and hands-on experience. This is not mere note-taking; it’s the ability to turn unstructured information into knowledge that is documented, organized, and referenceable.

- The Operator. Adept at taking an idea, concept, or policy and operationalizing it in a scalable way. Operators add repeatability, auditability, and instrumentation to business processes so these workflows can scale as business needs change. Operators ensure that the right feedback loops exist (with metrics identified, tracked, and reported at the right points in the process) to measure and improve efficiency and effectiveness while meeting or exceeding quality standards.

- The Analyst. Can pull data from different sources, integrate them into a coherent whole, and draw actionable insights that inform day-to-day decisions and long-term planning. This skill is especially critical if you want to measure progress against team objectives and craft compelling narratives about the team’s impact.

- The Technician. Able to identify, document, and specify the team’s automation requirements based on their deep knowledge of the technology stack (including its capabilities, limitations, and workarounds). Has the attention and respect of engineers and data scientists.

Unsurprisingly, large and mature policy teams afford more opportunities to specialize and go deep on specific personas, while smaller teams will prize breadth, where a single person can be mapped to multiple personas.

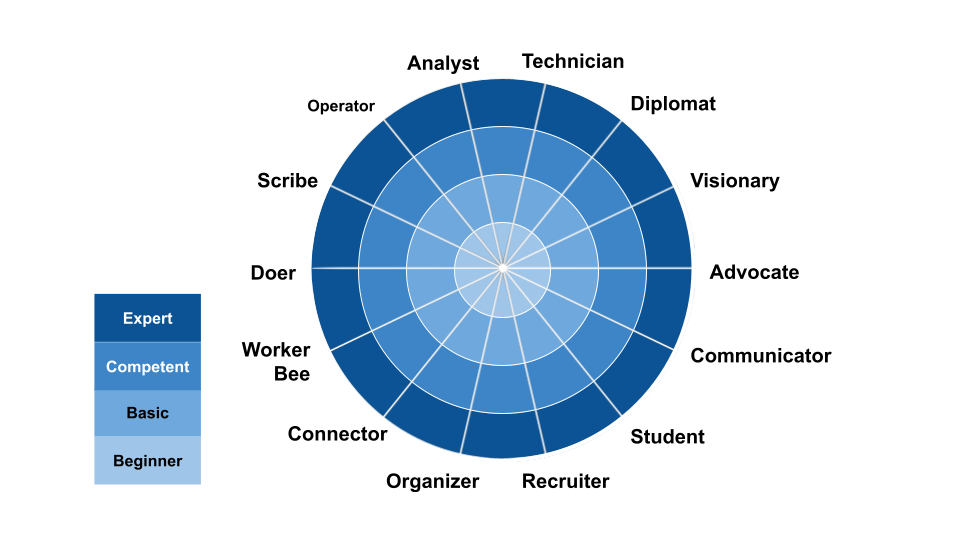

Regardless of team size, however, a long-term Policy career requires Basic to Competent levels of proficiency in most personas as a foundation. Individuals who start specializing too early in too few of these personas will have limited effectiveness in the long run, which can hinder their ability to move into more senior positions.

Practical Ways to Use Policy Personas

When everyone on the team is familiar with your list of Personas and their definitions, you can use these Policy Personas to do any of the following:

- Review the Team’s Composition. Any persona that is not adequately represented on your team is a potential capability gap. Map each team member to your team’s personas, then review the team as a whole. Are you over-represented for some personas and missing others? Do critical personas all map to just one person (who happens to be overworked)?

- Set expectations on assignments. When the personas are part of the team’s vocabulary, you can say, “I need you to be a Diplomat with these stakeholders,” and the full weight and meaning of that persona’s definition is conveyed in a simple sentence. You can also use personas to highlight how the team’s focus shifts over time (e.g., “We were in Advocate mode last month while we were lobbying to get our projects added to the plan. Now that the plan is final, let’s drop the advocacy work and focus on being Doers for the projects that made the cut.”)

- Add structure to development conversations. Ask team members and their respective managers to jointly assess the individual’s proficiency against each persona and then compare notes (e.g., plot individuals against the persona radar chart at the top of this post). In what areas would the employee need to grow to do their job well? What personas would they need to strengthen to prepare for an upcoming assignment? Together, the manager and employee can identify and agree on the personas that the employee will work to strengthen in the near term.

- Assemble teams. When a new project needs to be staffed, we tend to think in terms of individual people rather than personas. Rather than jumping straight to naming names, consider first asking what personas the project needs for success, then map specific team members to the personas. if you have no choice but to assign people who are not a great fit for the required personas, the mapping will highlight the skill gaps and risks in your team composition and remind you to keep a watchful eye on those aspects of the project

- Assess applicants. We tend to look for specific personas when we’re interviewing to fill a role but we’re not always aware of what we’re doing. By using personas (e.g., “We need a Policy Specialist who’s an excellent Student), we make these unconscious requirements explicit and increase our chances of hiring the right person.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. Isn’t a persona just a job description?

Not quite. A persona is an abstract definition that can be mapped to multiple jobs. A single job can require multiple personas.

- Personas are abstractions; job descriptions are context-specific. Job descriptions are often written for a particular policy area or subject matter; in contrast, personas are abstractions or meta-descriptions. For example, the Worker Bee persona can map to jobs like User Safety Agent, Legal Policy Agent, or Spam Analyst. The actual job descriptions for these roles can be quite different and require different skills, but the Worker Bee persona applies in all three cases.

- A single job description can require multiple personas. Certain personas commonly occur together or are commonly needed together in a single person to meet the demands of a job. Thus, a single job description can map to multiple personas.

A well-written job description will have each of its required personas represented under “Responsibilities” or “Requirements.” For example, a Policy Lead job description may have these four statements, which map to four different personas.

- Builds and strengthens relationships with stakeholders—Diplomat

- Excellent verbal and written communication skills—Communicator

- Sets the team’s strategic direction—Visionary

- Navigates internal politics to get things done—Doer

2. Can you give me a sample mapping of Jobs to Personas?

The table below offers a mapping of common Policy job titles to Personas. It’s not an exhaustive mapping; it is meant to be illustrative. Your team’s mapping will depend on the personas and jobs you’ve identified.

3. How do I map these Personas to my company’s job levels?

Below is an example of how the Diplomat persona could be mapped to Job Levels. Junior job levels generally have a smaller scope or scale of impact than senior levels.

- Junior Level: Works well with teammates, has no drama or tension with others, is generally well-liked, and is a welcome addition at any meeting or project.

- Associate Level: Able to step in as an impartial arbiter to resolve interpersonal disputes within their team, always keeping things professional.

- Mid Level: Able to act as an arbiter to resolve interpersonal disputes across partner teams and foster alignment on issues with their counterparts.

- Senior Level: Resolves team-level disputes between their team and other teams and helps stakeholders reach a consensus on a strategy, policy, or initiative.

4. What do you mean by Proficiency? Can you give me an example?

Below is an example of how the Operator persona can manifest at different levels of proficiency.

- Beginner: Able to follow an existing, well-defined process consistently. Can understand the process metrics that are collected at face value.

- Basic: Able to identify pain points in an existing process and use existing QA practices to improve the efficiency and accuracy of the process. Suggests process improvements that are locally optimized for their team’s benefit.

- Competent: Able to articulate principles that create “healthy” multi-team processes in a small to medium-sized organization. Can propose holistic improvements based on these principles and implement them.

- Expert: Able to define new or innovative ways to reimagine an existing process. They can also define a workable process for an entirely new subject area or line of business.

The above example assumes four proficiency levels: beginner, basic, competent, and expert. Each organization will have its own standard (e.g., see the NIH proficiency scale, which uses five levels). Use whatever leveling system makes sense for your team to reflect a continuum of mastery from intro-level theory to expert-level application or practice.

5. Do personas only apply to policy teams?

The use of personas can certainly be extended to non-policy teams. However, the exact combination of personas needed by any team will naturally vary depending on the nature of the team’s work.

Conclusion

The Policy Personas presented in this post are by no means exhaustive; they’re meant to be a starting point for creating a list that makes sense for your team.

- All policy teams, regardless of size and maturity, can benefit from using Personas as handy shortcuts in everyday conversations. Use them to verbalize expectations on assignments, add structure to development conversations, and give team members a practical mental model for thinking about their careers.

- Small or newly formed policy teams can use Policy Personas as a framework to formalize or refine job descriptions, career ladders, and job levels.

- Managers can use Policy Personas to review their team’s composition, assess candidates, and assemble teams in a more thoughtful way.

Unlike job titles and job descriptions, which are used during recruitment and promotion deliberations and are otherwise forgotten, Policy Personas lend themselves easily to daily use in regular conversations and meetings. They equip teams with a shared vocabulary, which is an essential element for any high-performing team.

Bibliography

Kalil, Thomas. “Policy Entrepreneurship at the White House: Getting Things Done in Large Organizations.” Innovations: Technology, Governance, Globalization 11, no. 3-4 (2017): 4–21. https://doi.org/10.1162/inov_a_00253.

Author’s note: The idea for this post emerged from a conversation with SM; thank you for bouncing ideas with me! My thanks also go to DH, YR, and IR for their incisive questions and feedback, which helped me express my thoughts in this post. If you decide to document and socialize your team’s list of Policy Personas. I’d love to hear about your experience. Email personas @ mdynotes.com to get in touch.